NOTE ON THE URN

February 10, 2025

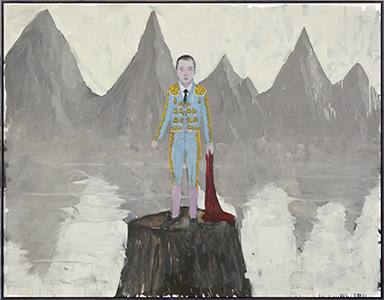

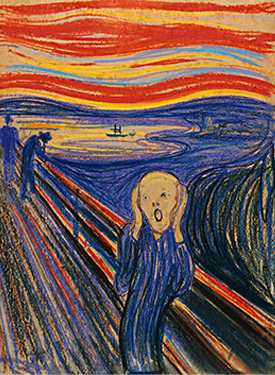

The painting above, The Urn, is part of my new body of work, The Wilderness. Some of you might recognize the doors and a simplified interior of Picasso’s last studio.

This body of work emerges in fragments that sometimes feel like remembered, half-faded scenes or dreams. The wilderness of the title is both outside and inside. It is the wilderness awaiting consciousness as it takes in the world, and it is the largely unexplored wilderness within ourselves.

I’m interested in charged fragments with some narrative explosion ticking inside them, but not in storytelling or ready-made myths, because I don’t think they have much to do with the power of a work of art. So, I don’t like to talk too much about images, which is always the easy place to go for representational work. However, it seems worth mentioning that for this exhibition, I’ve worked with interiors and the idea of the artist, which are not typical in my work. Houses, buildings, stairs, partly open doors at the cusp of an event. For the first time, I’ve been concerned with painting the artist, a reflexive gesture that attends to the one who gives attention, which in our day-to-day efforts amounts to desperately trying to use the fleeting time life offers to grasp the ungraspable. Maybe the most consequential aspect of the artist’s work is the effort to find significance amid impermanence.

The Wilderness, like many of my projects, is also concerned with painting—what it is, how it comes about—and the relationship between painting and poetry.

Above

The Urn, 2024

Oil and wax on canvas

72 x 60 in.

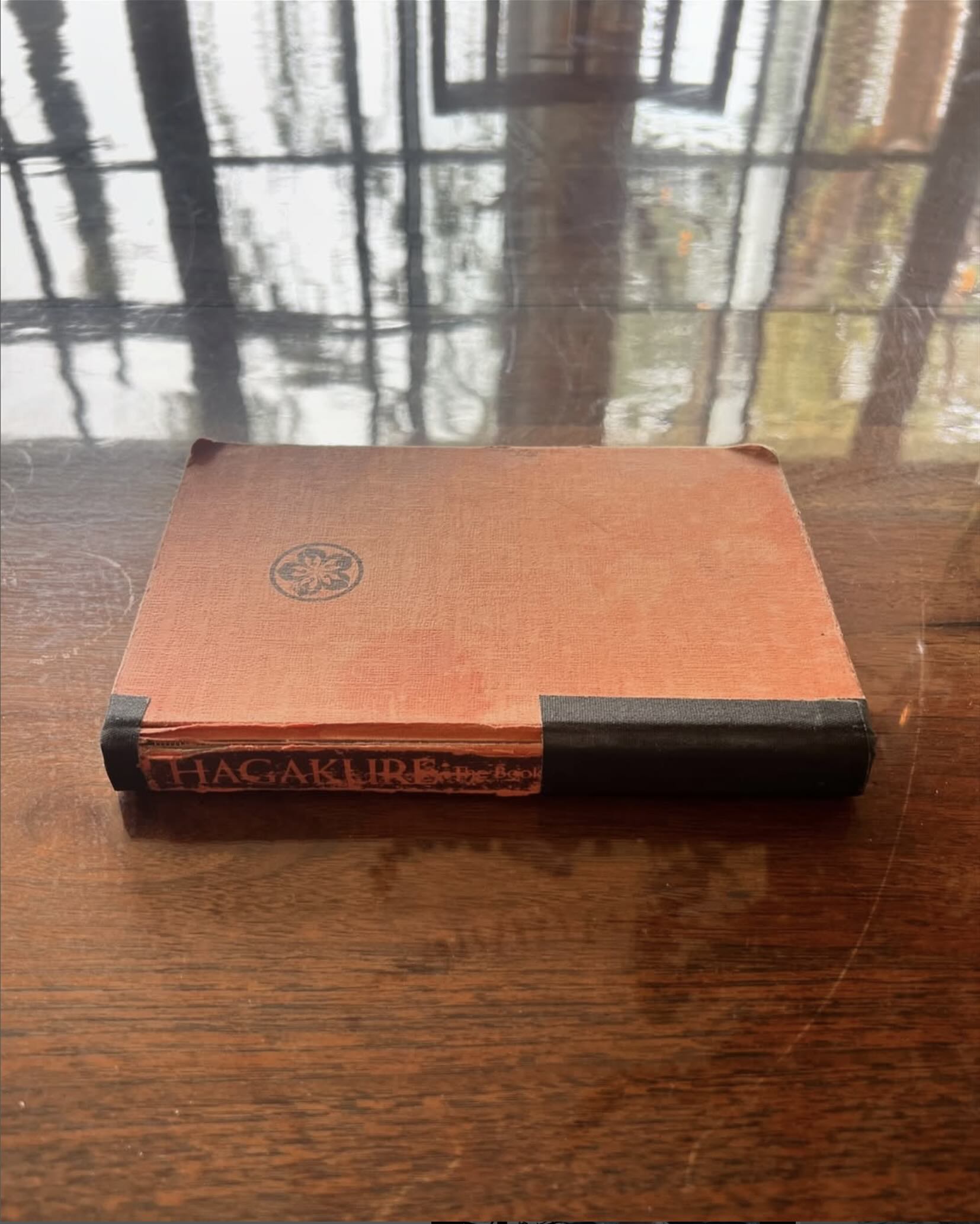

NOTE ON HAGAKURE: THE BOOK OF THE SAMURAI

January 27, 2025

There are many books that have shaped my understanding of meaning and purpose and their connection to art and life. What one of them would offer me was not immediately apparent when I first encountered it in my early twenties. It has since become a consistently clarifying and calming guide in my life. If you are tired, overwhelmed, angry, or saddened by the increasing normalization of confusion, spectacle, and dishonor, I suggest spending some time with Hagakure: The Book of the Samurai by Yamamoto Tsunetomo.

It is not a self-help book, and parts of it might seem extreme or irrelevant to your life. However, the book offers a way to think about purpose, meaning, and drive in a life guided by commitment and clarity of intent, where purpose arises from aligning one’s actions with an inner code of honor and discipline. Like Viktor Frankl in his book, Man’s Search for Meaning, Tsunetomo suggests that meaning is found through dedication to the present task, no matter how mundane or fleeting, and warns that drive without purpose can become aimless and destructive. His reflections stress the importance of living fully and authentically in each moment. Instead of being paralyzed by fear of failure or uncertainty about outcomes, the samurai’s focus is on engaging with life wholeheartedly, here and now.

In his words, “There is surely nothing other than the single purpose of the present moment. A man’s whole life is a succession of moment after moment. If one fully understands the present moment, there will be nothing else to do, and nothing else to pursue. Live being true to the single purpose of the moment.”

NOTE ON THE GNAWING

December 3, 2024

Before discussing my new painting, The Gnawing, I want to offer a qualification about what I have to say. I have spoken—and continue to speak—about art in general and my work in particular, as I am doing here. This is likely for the same reasons I have always been drawn to physics, philosophy, and literature: I’m curious about what things are and how they function. For these and other motivations, I still value sharing aspects of my practice and what I find relevant about art and artmaking. But I trust that value less than I once did. The older I get, and the more time I spend trying to bring a painting or sculpture into being, the clearer it becomes that what is truly at stake in the work escapes the narratives we propose or assume to be explanations. Increasingly, I find that such explanations provide a misguided confidence in arguments or symbols that rely on cognitive processes, while anyone who has deeply reflected on what constitutes a transformative experience with art recognizes that other processes ineffable and unknown are at work. In fact, the power and revelation of an artwork seems to be inversely proportional to our capacity to explain it.

What makes an art experience transformative—rather than merely entertaining, instructive, or fashionable—is its capacity to reveal direct knowledge, something whose emergence or consequences are difficult to grasp with words. So why bother saying anything at all? I often ask myself this, but for now, I’ve settled on the belief that words worth speaking are those that point beyond themselves, opening a space for direct experience. I have certainly benefited from the writings of poets and artists reflecting on their work.

With that as context, let me now say something briefly about transformative art, my practice as a whole, the relationship between presence and reference, and finally, The Gnawing.

What makes an art experience transformative is irrelevant or invisible to many, and it’s a quality or a set of qualities that resists recipes or rules. It’s likely this combination of resistance, invisibility, and irrelevance to conventional expectations of art that explains why most art operates primarily as cultural production, decoration, currency, entertainment, or the illustration of ideas or feelings—or some mix of these, all forms of mediation, far removed from direct knowledge. Regardless of how naïve it might seem to some, or how mysterious, challenging, frustrating, and potentially disillusioning it may be to seek a transformative art experience rooted in direct knowledge, for me, it’s not just a good reason to be an artist—it’s the only reason.

Yet, intentions and motivations only take us so far—something I didn’t need life to teach me, though it did anyway, shaping my art practice along the way. Over time, my studio habits and challenges evolved into an art practice, which eventually expanded into a life practice—a life practice because I found no defensible boundaries between my choices, values, and conduct, whether inside or outside the studio. Today, I like to collide exploration and experimentation with contemplation, discipline, and respect. The meaning in my work is less something I impose and more something I seek to uncover—an uncovering made all the more radical and urgent by the pursuit of a transformative art experience. This imperative often leads me to destroy or rework pieces, which is why, although many of my works do leave the studio, my practice remains fundamentally distinct from one focused on production.

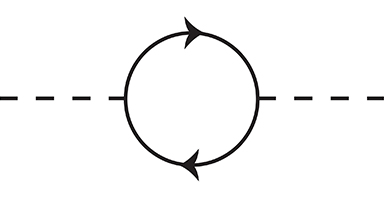

Despite—or perhaps because of—whatever knowledge of art I possess, my day-to-day practice depends just as much on intuition, accidents, frustrations, and love—elements that are often absent from the narratives we construct to “explain” the work. Many other events and beliefs also shape my practice. One of the most influential is the relationship I want between presence and reference in a work of art—a dynamic I often consider using the tools of my training in quantum mechanics. I consider a painting complete when it finds an equilibrium between the references suggested by the imagery, the presence of the work itself, and the performative gestures embedded within it. This equilibrium is precarious—a balance of forces that creates a charged, unstable stasis.

References, as I use the term here, are nodes of meaning, and I’m most interested in those that function as conduits between the ordinary and the ineffable. They anchor the emotional and intellectual landscape of the work, connect spirit and matter, and point to what remains unsaid or perhaps unsayable. For the most part, the individual image elements in my work are not intended to be clever or to signal sophistication or virtue. Like many poems, they aim instead to isolate and recontextualize details, defamiliarizing the familiar, heightening awareness, and reshaping understanding. I want these images to elicit a dual movement: one toward immediacy, rooted in sensory experience, and another toward reflection, propelling consciousness into realms of metaphor, memory, and philosophical inquiry.

The presence of a work of art, however, operates a different way. It transcends the sum of its symbols, materials, and references, becoming a phenomenon that resists reduction. Unlike an assemblage of signs pointing elsewhere, a work of art establishes a self-contained world—a charged field of Being that exerts its force through encounter. Presence is more than objecthood. It emerges from the materials and embodied processes, as well as the life force the artist imbues into the work. This presence shares with relics the capacity to exceed physicality, holding and emanating meanings that are neither fully accessible nor entirely withheld, and often standing as a witness to something beyond itself. The power of such presence lies in its refusal to resolve the tension between recognition and mystery, compelling not interpretation but existential engagement.

The painting The Gnawing (2024) is an example of how these ideas about presence and reference unfold in practice. Like all of my work, what I was after while making it was to bring about an experience that is moving and immediate. Its presence asserts itself in the space, not only because of the painting’s size but also because of the feeling of its dislocating imagery and by paint that serves both to render and to disrupt what is rendered.

At the top of a staircase, an open door allows light to seep into a dark room, maybe a basement—not enough to illuminate it, but enough to point to a world outside. On the stairs lies a battleship whose scale is unexpected. It’s too small to be what it claims to be and too big to be a toy. Its prow touches the basement floor, as though it has reached its end or paused mid-motion, awaiting something. The angle of the stairs makes me think of the walkway to a funeral chamber, and the open door, with its sickly light and blocked by the ship, is not a way out. The boundaries of this confined, unarticulated room are blurred by swirling paint. These paint passages do not describe objects but evoke the air itself—thickened, blurred, and weighted like the texture of memories. The shadows stretch and deepen, as though the room itself shifts, unsettled and unstable. The atmosphere of the room seems to be one where meaning is being fought. The ship’s descent hints at a fragment of narrative, but the larger story remains unavailable. Is this battleship something in itself, or a stand-in for something else? Is it a tombstone of something or someone—perhaps another self, no longer retrievable?

We are left to contend with a moment that is less concerned with how it came about than with its consequences. What the painting offers is an existence in the aftermath—a permanent state of “afterwards.” The battleship, an emblem of conflict, resolve, and violence, has been repurposed as a model, a make-believe, a disarmed weapon, reduced to something toy-like and uncertain. In this sense, it could suggest the vulnerability of something pretending to be more than it is, birthed into a world where reality and fiction are difficult to distinguish. What is really being born in this wood canal between light and dark? I want to say loneliness, but I could also say longing, or dreams—all three are tears of waiting.

The access the open door could offer is something that it appears indifferent to. This door neither promises clarity nor comments on the darkness below. Its painted light is incidental, a reminder of the inaccessible and featureless outer world that contrasts with the basement’s restless shadows. The paint and the painting cannot resolve the contrast between the two spaces—the external and the internal, the lit and the darkened—and so, the battleship, like any object or feeling that’s brought into this room, becomes subject to the ambiguity of its surroundings. If this battleship belongs somewhere now, it is in the dark room where objects are held not as they are or as they hope to be, but as relics reshaped by shadows—haunted by a gnawing sense of banishment from a place barely remembered and bearing witness to mourning for what can never be released or fully accounted for.

THE ILLUSION OF VIRTUE

October 28, 2024

I often hesitate to give my honest opinion on artists whose work I don’t admire, as critiques can be hard to hear, may seem ungenerous, and are easily misunderstood. However, someone I know and respect recently asked for my thoughts on Njideka Akunyili Crosby. I wrote the text below in response, and I now feel it should be included here with my other notes.

Before turning to her specifically, I should lay out what I believe to be the core of the art experience. Not all art, but what I consider great art, is a form of direct knowledge—an unmediated awareness, untouched by narrative, pleasantries, political relevance, analysis, or explanation. This type of direct knowing feels as if something has shifted within you, a change not driven by understanding or insight but by something far less tangible, something that bypasses cognition. It’s not unlike what one might experience in a moment of religious clarity or under the influence of a powerful psychedelic.

This, for me, is what art must be. Anything short of that—be it enriching, entertaining, enlightening—is, at best, a distraction, perhaps even a pleasant one, but not what I seek in art. In fact, I wouldn’t even call such encounters “art.” Yet they are too often called just that, and when fashionable, “great art.” But trends exist solely in the realm of conventional knowledge—the cognitive, educational, transactional, and social. True, direct knowledge doesn’t entertain the crowd because it resists translation; like a religious experience, it defies gossip, and, by its very private nature, is set apart from the interests of trendsetters and those who trade in the currency of social opinion.

Njideka Akunyili Crosby’s work, to me, is accessible, decorative, and facile. It finds a receptive crowd because it delivers a "message" that is readily grasped, giving viewers a sense of virtue as they acknowledge her themes of family, cultural hybridity, and post-colonial identities. These themes, however, are treated in a reductive way that feels almost cursory, akin to an introductory sociology lesson. Her work is both familiar and "different," like looking at a foreign country through the window of an air-conditioned bus—a 21st-century echo of 19th-century Orientalism. Her domestic scenes and ornamental compositions convey warmth and familiarity, a seeming confrontation that remains cozily superficial. This aestheticizing of African life sidesteps the uncomfortable, the rough edges of African reality.

Even if I believed the museum or gallery were a proper stage for political work—which I don’t—her paintings seem to undermine such an aim. They cater to an expectation of political engagement that is populist and shallow. True political art is rarely welcomed in polite company, much less in the comfort of one's living room. Her work is a form of virtue signaling, providing illustrations that appeal to those looking to soothe either personal ambition or unease.

When she speaks of her work, it’s usually in fragments—a story about a fabric, a mention of family history. Such anecdotes are easily grasped, offering something manageable for her audience to take home. A more rigorous, demanding exploration—one that resists these easy morsels—is rarely popular. People seem to want “more,” which often means “less.” They rarely want to truly experience what’s in front of them. They almost never want to hear ideas that require deep introspection. Instead, they want what meets them comfortably, what reassures rather than challenges them. They want a fog of understanding, something removed from the real and immediate, which is, of course, worlds away from direct knowledge. They seek “generous tales” because a hard encounter with truth could disturb the self-image or social façade they’ve constructed.

I’ve listened to her talks, and they are painful in their ease. She keeps to accessible stories, avoiding depth, because this is what pleases the crowd. In art, unfortunately, many people are content with a visual soundtrack to their lives. Occasionally, she engages with popular racial or cultural theories, but these remain shallow; her discussions skirt past the profound, hovering at the edges of post-colonial identity or critical race theory. She mentions specifics—photographing Nigerian architecture, sourcing local fabrics—but rarely connects these elements to broader questions of appropriation or globalism that might deepen the intellectual weight of her work.

She is very popular, so my opinion is not shared by many. In the art world, stories, spectacle, trends, and market success are too often mistaken for encounters that transform. There are reasons for this, of course: the appeal of trends and virtue signaling, the expediency of giving people what they want, and the lure of spectacle and social approval. But the deeper cause for this confusion, I suspect, is that they have never experienced a genuine transformation in art—either life or courage has not placed them in a position where they could receive it.

Although my words may sound tough and ungenerous, I believe they are compassionate. They are spoken on behalf of the values and artists who have given the best of themselves, sacrificed much, and held to their integrity to show us what is possible. It is to them that my voice is indebted.

THE CULT OF IGNORANCE

July 26, 2024

Always, but especially at this political and historical moment, we must fight against ignorance—often militant, arrogant ignorance—masquerading as alternative knowledge or healthy skepticism. We should also combat the related reverence for distraction and fame over quality and integrity.

In his 1980 article “A Cult of Ignorance,” Isaac Asimov wrote:

“There is a cult of ignorance in the United States, and there has always been. The strain of anti-intellectualism has been a constant thread winding its way through our political and cultural life, nurtured by the false notion that democracy means that ‘my ignorance is just as good as your knowledge.’”

This passage is as relevant today as it was in 1980. But the cult of ignorance was never, and is even less so now, only a United States problem. Look around the world.

We need to fight ignorance because important values, knowledge, and institutions that took years to build are at risk. We need to inform ourselves about what real expertise is and be very careful with conspiracy theories about science or anything else. Speak and educate others if you are a real expert on something—besides your opinion. Consider not echoing theories you don’t understand. Respect the skepticism that comes from informed, honest inquiry, and reject the undermining of truth that results from fear or dubious agendas.

It’s clarifying to remember that the fresh perspectives that occasionally come from lack of expertise rarely take the form of ranting anger against the beautiful, and sometimes unbearable, insights and discoveries we have managed to achieve.

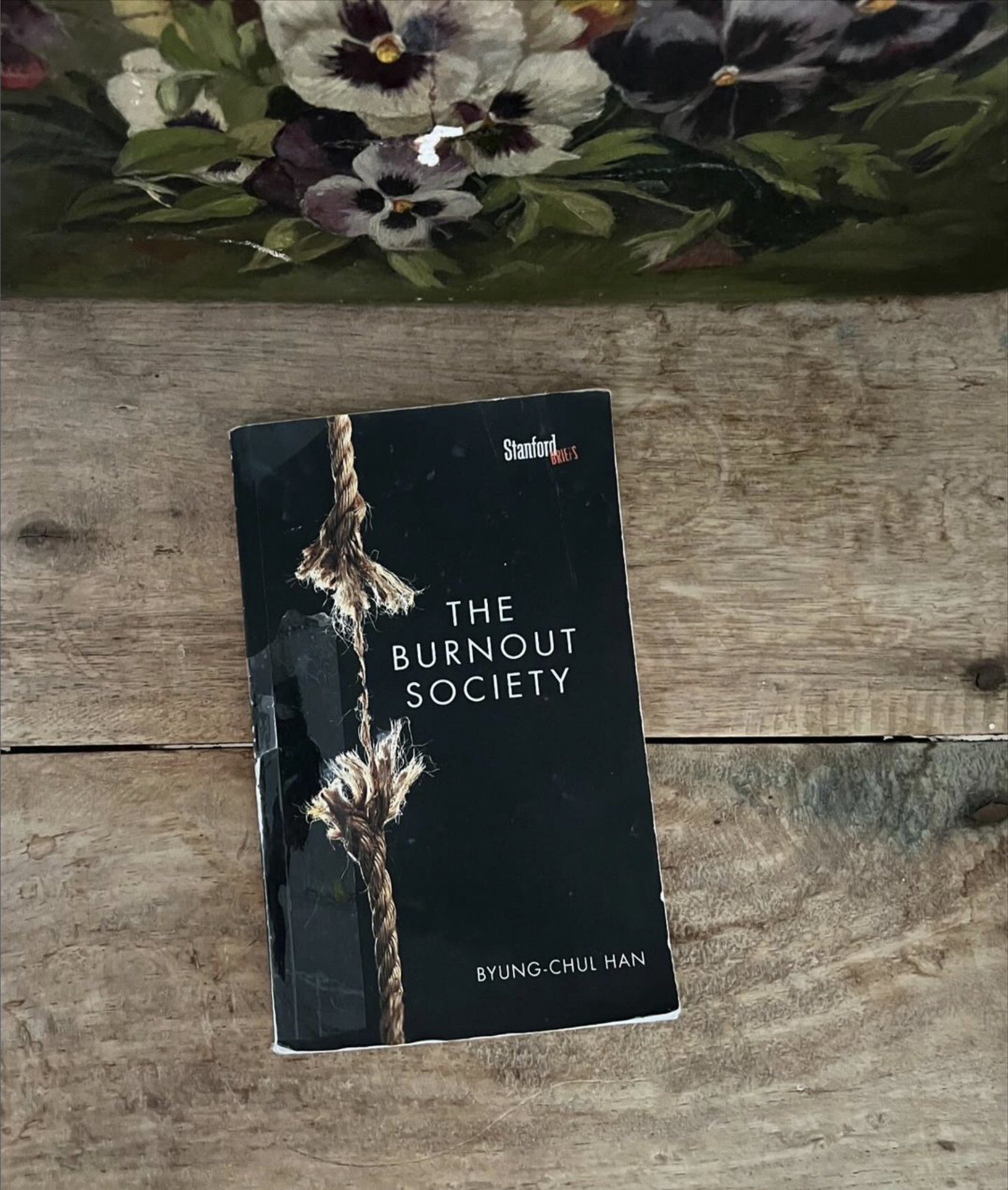

NOTE ON "THE BURNOUT SOCIETY"

July 7, 2024

I hope you are having a good Sunday. I woke up thinking I should say something about “The Burnout Society” by Byung-Chul Han.

This short and relatively easy to read (though philosophical and demanding) book is helpful in understanding aspects of the contemporary spirit and the nature and causes of artistic disenchantment.

Many artists, gallerists, curators, and collectors today are caught in a cycle of self-exploitation, striving for recognition in ways that often go against what initially made art meaningful for them. Their pursuit of success, lack of attention to genuine experience, and the demands of the art market frequently lead them to numbness and cynicism towards art and life, as well as significant emotional and mental health challenges. To make matters more absurd, these pursuits often stem from borrowed ideas of success and value rather than self-knowledge and earned understanding.

Han explores the pervasive culture of self-exploitation and relentless self-optimization that defines much of contemporary life. He argues that the shift from external disciplinary forces to internalized pressure has led to widespread feelings of burnout, anxiety, narcissism, and depression. In the traditional master-slave dynamic (Foucault and Marx, for instance), power and control were clearly delineated, with the master exerting authority over the slave. By contrast, Han argues that in modern society, individuals have internalized both roles, becoming their own masters and slaves, driven by self-imposed pressures for constant productivity and success. This internal duality blurs the lines of exploitation, as people push themselves to exhaustion, embodying both the oppressor and the oppressed.

This book is not for everyone—no book is. Many people have found it dense and thick with jargon. Some critics have also argued that Han’s analysis is pessimistic and deterministic, and that he oversimplifies the nature of depression, downplaying the role of biological, genetic, and individual psychological factors that contribute to mental health conditions.

If you have read “The Burnout Society,” I’d like to know what you think.

NOTE ON "HERE TO KNEEL, VOYAGERS"

June 15, 2024

Since I started as an apprentice in my early teens, I have been interested in paintings that incorporate words, images, poems, material presence, drawing, and that, while superficially representational, are neither scenes nor aim to look complete in the sense of a fully decorated rectangle. Two years ago, these interests took new form in the paintings currently on exhibition at the Museo de Bellas Artes de Cuba. This body of work incorporated architectural elements rendered in charcoal, words, and seemingly disconnected image fragments. I continued this exploration in a group of paintings and sculptures that will soon be installed at the Hispanic Society in New York.

"Here to Kneel, Voyagers" the exhibition I have created for Patricia Low Contemporary, continues to explore and expand the territory suggested by those two previous projects. This body of work integrates nuanced observations of transitory experiences with enduring concerns, such as redemption, memory, time, myth, and nature. The paintings and works on paper bring together complete and incomplete parts, where painted figurative details and images of nature coexist with sketchily drawn—often in charcoal—seas, architectural references, words, or lines of my poems. Aspects of these works are characterized by images with uncanny or charged allusions and poetic language, while other aspects seem incomplete or silenced. I am trying to extend the boundaries of language, images, and of the paintings themselves to articulate the unspoken as well as the unspeakable, in order to open a space for imagination and deeper emotional engagement with the artwork.

PRELIMINARY NOTES ON “THE GRIEF OF ALMOST”

June 8, 2024

OVERVIEW

This is an environment consisting of four large paintings and a monumental sculpture, centered around the motif of an apple tree and incorporating references to fire, ice, night, and the exilic projection of a utopian home. This project is concerned with the innate drive for self-realization and the search for—and obstacles to—a meaningful life. While not explicitly about Robert Frost or his poetry, during the process of creating this body of work, I have considered elements from the poet's life and poetry to construct a narrative that transcends individual life specifics, engaging instead with existential, philosophical, and societal questions.

Robert Frost’s family has been a recurrent source of reflection during the creation of this exhibition, in particular, the relationship between Robert and his son Carol, and in a more general sense, the relationship between parents and their children. While Tolstoy noted, "every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way," I find that Frost's family, occasionally bucolic and frequently tragic, along with his poetry, raises numerous questions pertinent to many aspects of our lives. These questions explore hopes, challenges, and tragedies that, though initially appearing recognizable, tend to elude understanding. They are relevant to me because I am both a father and a son, and also because filial exchanges frequently model and inform many other dynamics and aspects of the experience of living. As I see it, the tensions, hopes, promises, and regrets present in families are at the heart of the human condition and shape our self-understanding.

As the project evolved, three visual elements allowed me to consider those questions and became the main forces pulling everything together: the apple orchard, the night, and the generative tension between fire and ice. In addition to these visual elements, my concerns also included the landscape around New Hampshire and Vermont, the implacable nature of poetry, and the desire to create an immersive and interactive poem whose final embodiment depends on community participation.

Through the imagery, notably the apple tree and the night embodied in an airplane, as well as the interplay between the images and their execution, the narrative explores themes of loss and separation. The apple orchard, once a symbol of sustenance and connection, becomes the scene of ultimate banishment, severing not only their connection to the land but also to each other. This expulsion from the orchard brings forth themes of exile and the consequences of decisions made, touching on broader themes of human frailty, redemption, and the ongoing search for identity and belonging amid irrevocable change and, ultimately, death.

The four paintings present a cycle that begins with hope and ends in catastrophe and redemption, then starts again. The imagery invokes a lush harvest in winter, an orchard in the sky, a burned landscape, and an apple tree against an ominous ocean. The two figures that appear, a handless boy and a falling, burnt man, are both maimed, though in different ways and by different forces. The plane of night descends upon the room, dragging with it an uprooted apple tree—did the plane rip it out of the ground or merely transport it as such? My goal is for the dried-up apple tree to live again with the writings and poems visitors will clip to its branches. These writings will remain secret and, in this way, connect with Carol Frost’s unknown poems.

THE ORCHARD, FIRE AND ICE, AND THE NIGHT

The apple orchard stands as a frequent and complex symbol in history, myth, and literature. It connects to ancient stories, such as the Edenic garden and the Hesperides' golden apples, highlighting themes of knowledge, sin, and the pursuit of the unreachable. As a symbol, it reflects the natural cycle of growth, decay, and renewal, showcasing nature's resilience and the inevitability of change. On a metaphorical level, orchards represent human choices and their consequences, underscoring the notion that beginnings are often hidden within endings. The orchard, in its simplicity, serves as a backdrop against which the complexity of human existence is explored, revealing that within the natural cycle lies deeper insights into life's transient yet recurring patterns.

Robert Frost's relationship with apple orchards extends beyond the pastoral imagery found in his poetry; they are emblematic of his personal and philosophical engagement with nature, work, and the New England landscape that he loved. Frost's life was closely tied to rural settings, where he owned and operated a farm in Derry, New Hampshire, for nearly a decade. This experience deeply influenced his poetry, with apple orchards frequently serving as a setting for his exploration of themes such as community, isolation, labor, and the passage of time. The orchard should also be understood as part of the myth of the farmer-poet created by Frost himself. In his poetry, Frost's apple orchards often embody the tension between chaos and the human impulse to order. This dynamic resonates with Frost's own life, in which he often—particularly in the period between 1934 and 1940—struggled with the need to order and endure catastrophe.

Frost's interest in, and self-myth of, being a farmer was carried on by his son, Carol. In the 1920s, Frost had a busy life, so the farm he had bought in South Shaftsbury, Vermont, was with the hope of planting a new “Garden of Eden” run by his son, and Carol’s wife, Lillian. Frost wrote to a friend in 1925 that “I always dreamed of being a real farmer; and seeing Carol as one is almost the same as being one myself. My heart’s in it with him.” Carol continued the farm through the 1930s but with diminishing success while being supported by his father, which contributed to his depression, anxiety, and lack of self-worth. He hoped to leave Vermont and the yoke of that life, moved to Florida, and, unfortunately, pursued a career as a poet. But towards the end of 1940, after several days of darkness, Carol shot himself with a rifle and was found by his son, Prescott.

I understand the image of a pivotal night as the "night of nights" as a critical point where fate intersects with mortality. It points to an evening of significant importance, a way of emphasizing that a particular night stands out above all others. I’m interested in how this night of nights had been coming toward Carol—and is coming toward us—for some time. It’s a plane of darkness that has been chasing us from birth—or perhaps, after a generative event—and lands on us on a fateful night. This night of nights embodies the factual intersection of human life with the inescapable reality of death, marking a point beyond which an individual's fate is irrevocably changed.

In the installation, two other important elements are fire and ice. The tension between fire and ice serves as a potent metaphor pointing to extremes of human emotion and the dualities of existence—passion and indifference, destruction and numbness. As we can see in this brief excerpt, in his poem Little Gidding, T.S. Eliot offers fire and ice as destructive forces and as symbols of purifying transformation,

- When the short day is brightest, with frost and fire,

- The brief sun flames the ice, on pond and ditches,

- In windless cold that is the heart's heat,

- Reflecting in a watery mirror

- A glare that is blindness in the early afternoon.

- And glow more intense than blaze of branch, or brazier,

- Stirs the dumb spirit: no wind, but pentecostal fire

- In the dark time of the year. Between melting and freezing

- The soul's sap quivers.

- In Frost’s poem, Fire and Ice, fire and ice represent the potential end of the world,

- Some say the world will end in fire

- Some say in ice.

- From what I’ve tasted of desire

- I hold with those who favor fire.

- But if it had to perish twice,

- I think I know enough of hate

- To say that for destruction ice

- Is also great

- And would suffice.

Finally, I would like to briefly mention the sea. The sea, which has been important in many of my projects, appears here with two goals: to point to a specific longing—Carol’s desire to relocate to Florida and write poetry—and to suggest the ephemerality of human life and the permanence of nature.

A BRIEF HISTORY OF THE PROJECT AND MY INTEREST IN ROBERT FROST

Now that I have outlined the project and a few elements and ideas pertinent to it, I would like to say a few things about the history of this project and my relationship to Robert Frost.

Since my early twenties, I have been interested in the poetry of Robert Frost. When I was first asked to do a project for the Hood Art Museum in the spring of 2014, the possibility that Wilson Hall, the former library, might be included as part of the new museum made me think of the young Robert Frost and the impact that his encounter with a poem there had on him. In 2015, I came to Dartmouth as a Montgomery Fellow and worked on my ideas for the exhibition by sifting through the poet’s archives at Rauner Library and by visiting his former house in Derry, New Hampshire. Although the historic Wilson Hall did not become part of the museum's final architectural vision, my motivation to pursue a project that explored ideas important to me through a dialogue with aspects of Frost's biography had already taken root by the time I returned to Dartmouth in 2016 as a Roth Visiting Distinguished Scholar.

During that year, I used my walks through Pine Park to develop the ideas for the exhibition at the Hood. The contrast between the movement and changing light of the water of the Connecticut River and the stillness created by the tall pine trees and the soft pine needles on the ground made the park a good place for me to read Frost’s poetry and reflect on aspects of his life that seem easy to state in words but difficult to comprehend emotionally.

First, I want to highlight the importance of Robert Frost’s exilic spirit to my interest in his work. It seems unexpected to think of Frost, the quintessential American poet of the 20th century, as an exile. Yet, I recognize in the poet the restlessness, homelessness, and hope of re-invention that are characteristic of exiles. In the case of Frost, however, the former home is not a place so much as a void, a permanent longing without name or location. In his 1914 poem, “The Wood-Pile,” he comes closest to pointing to the specific quality of his elusive homelessness,

- The view was all in lines

- Straight up and down of tall slim trees

- Too much alike to mark or name a place by

- So as to say for certain I was here

- Or somewhere else: I was just far from home.

When there is no place to mark that one is here or elsewhere, the only thing we know is that one is "Just far from home." Not knowing where you are, the only marker of one's location that can be relied on is the one that tells us we are not where we belong—wherever that may be. This permanent homelessness and the consequent desire to find a place to settle—a home in which to reinvent life—might be one of the reasons why Robert Frost is known for saying, "I never went anywhere without wanting to buy a place there."

One of the distinctive characteristics of a an exilic condition is that the main thing, and maybe the only thing, we know about our location is that we are far from home. This foreignness of the place in which we find ourselves in turn bring about questions related to time, such as “how long have been traveling, and how long have I been here?” And so, it is not uncommon to find in the feelings of homelessness and homesickness a sense of uncertainty about time. In the case of Frost, he belongs nowhere, and this lack of belonging—despite the creation of the New England-farmer persona—also makes him a wanderer in time. He is from nowhere and is neither home in the present nor in the past, a condition that he often conveys in his letters. As far as I can tell, his rootlessness in time and place and his consequent search for a place to settle are not only central premises of his work and life, but they are also his emotional and intellectual fuel.

While this exilic condition seems to be an enduring trait in Frost’s life, in this project I am particularly interested in two periods of his personal and poetic biography: the early period between 1900 and 1914, and the period between 1934 and 1940, when he was close to my age now. My interest in these periods doesn't arise from a desire to retell or illustrate his life but rather to use aspects of his life and poetry, along with the connection between them, as points of engagement to explore the dynamics between hope and failure, fantasy and depression, the indifference of art to aspiration, negotiation across time between perseverance and regrets, and nature as a witness to the human dynamics.

For me, the connection between the earlier and the later period is a photo of Robert and Carol Frost leaning against a fence. I have a reproduction of this picture in my studio, along with two dried apples from the Frosts’ Derry farm. My interest in and reading of the photograph is influenced by the background I outlined in the introduction, but what the photograph provokes in me are mostly unfounded projections into Frost’s life that map out my concerns as a son and father, and my interest in time, memory, poetry, and art. Which is to say that this project is not about Frost but comes forth from elusive reflections and questions about art and life that use my myths and projections about the poet’s life and work to understand my own.

FOUR IDEAS I FIND USEFUL

January 10, 2024

PRUNING

Pruning a rose bush leads to the growth of robust new stems and encourages more blooms. There are many diseased but fancy looking rose bushes—some even have plastic-coated flowers for a longer-lasting appearance. Instead of pruning them into modest, unglamorous, yet potential-rich plants during winter, we often focus on displaying and boasting about the beauty and quantity of flowers on a troubled bush. Clarity, humility, and meaning come from pruning.

THE BEGINNER'S MIND

For the beginner, everything is open, but for the expert, few things are. Yet, beginners may find their openness limited by a lack of awareness of possibilities, restricted means, and inherited assumptions. On the other hand, experts, with their awareness of potential, broader means, and discarded inherited assumptions, sometimes have a more expansive view of what is possible. These ideas may seem contradictory, but they are not.

FREEDOM

Many believe, or at least suspect, that the greatest threats to our personal and social freedom are external forces controlling information, thought, and freedoms. However, two significant self-generated threats to our freedom are often overlooked. The first is our own tyrannical self-rule, demanding achievement and constantly checking our status and progress to validate our worth through others' recognition. The master-slave relationship, often used as a metaphor or framework to understand power dynamics, identity formation, and moral values should be reconsidered in the increasingly familiar situation in which we are both the master and the slave. The second way in which we avoid freedom is by exercising “our freedom to choose” from a collective, pre-defined menu of morality, concepts of the good life, judgments of quality, values, and “our freedom to be” banal, distracted, false.

THIS HAS NOTHING TO DO WITH YOU

Not an exhaustive list: hoopla about this and that; trending stuff; your superpower (you have none); someone’s opinion about who you are; the opinions of some fluffy guru; the dogmas of some expert; the bitterness of some hater; the latest thing; the place to be.

ENTRANCE TO THE LOS ANGELES STUDIO

September 15, 2023

Like all my studios, I designed and built this one not as a factory but as a hybrid between a laboratory, a monastery, and a place to gather. Like all my studios, bringing it to life took work. Things will always get in the way when you are at the edge of what you are able to do. If thoughtfully and sensitively considered, a studio-of any size-can keep us on our toes when we get too comfortable and offer us a place to rest when we are going nuts.

If considered and created properly, the studio-and also the home-can be a challenger, mentor, mirror, and force that sustains you when you need it most. Perhaps you are tired of inauthentic confessions, demands, and celebrations of awesomeness, or you are worn down by the confusion, desperation, and despair manifested in the cynicism around you. Perhaps you overestimate your challenges and settle for less than what you might be able to bring forth. Perhaps you hope enough external validation will confirm you are not what you fear. Perhaps you are prone to deception. Perhaps you have been led to believe that banality and reduced ambitions of the heart and mind are signs of sophistication.

The studio can help. Design not what you like but what you need.

CONVENT OF SAN MARCO, FLORENCE

May 9, 2023

During my two recent visits to Florence for my exhibitions, I saw and did many things that made my time there memorable. One of them was the opportunity to spend time at the Convent of San Marco.

The convent as a whole is extraordinary, but it was the frescoes Fra Angelico painted in the private space of the monk's cells I found most moving. These frescoes were not intended as means of instruction, still less as decorations, but as aids to contemplation and meditation. They are striking even in reproductions, so I have admired them for decades, but I was not prepared for what it felt to be with them.

It is not the grand viewing of museums. The cells are small and lit only by a single window. The frescoes are relatively high, and it is difficult to stand in front of them. And there are not many wall texts explaining the iconography, an omission I appreciate.

The morning I visited, the light that filtered into the rooms was cool and powdery, which made the dry surface and colors of the frescoes seem ethereal. Faced with these unpretentious, utilitarian, and luminous paintings, my first impression was one of tenderness. Then, their power became apparent, and the paintings in those cells brought forth truth that was indistinguishable from love.

On the way out, as I was passing the gardens, I felt grateful.

I realize that mentioning truth and love might be incomprehensible, laughable, or misappreciated in an art, cultural, and social environment like ours. But for some of you, these words will resonate. And for those of you who are fatigued or put off by the art world or the art you encounter, my suggestion is to keep looking.

Above

1. The Mocking of Christ (detail).

2. A cell with The Annunciation.

Fra Angelico, fresco, 1439-43

Convent of San Marco, Florence

THE STATIONS

February, 2023

I hesitated for months to start this cycle, as I was wary that paintings depicting the sea and flowers might come across as shallow and ornamental, but they kept coming back until one day I decided to accept the risk. I purposely didn’t ask myself why these paintings were insisting themselves. Instead, I painted and stared at them as they found their way into my studio. So, now that the series is well on its way, and I have spent many hours looking and writing, I reflect on what are these paintings of or about.

In part, they are about transientness. Transientness affirms the present and acknowledges its passing. The sea is never the same, constantly shifting with changing waves, light, weather, and shorelines. Similarly, flowers bloom and wither. In awe or casual amusement we take in their beauty and scent, and we mourn it because we know their brevity. Petals fall, colors are stained by time, and the scent is given to the air.

But transientness is meaningless without permanence, and permanence reveals what is enduring in the ephemeral. The sea is as it has always been: a permanent referent with which we measure and locate ourselves, a shaper of lives and definer of civilization and lifestyles, and a boundary, and a means to navigate. The flowers point to the continuity of life and stubbornness of the will to be, and they also stand for nature and the anti-entropy force in all life.

The horizon serves as the point where permanence and transience intersect, and the flowers mark this imaginary boundary. The sea and flowers are both eternal and fleeting, and these paintings explore the connections between these two opposing temporal conditions. Instead of trying to put a name to this intangible connection, I have compiled a list of words that may evoke its spirit: beginnings, hope, markers, belonging, preservation, presence, vanishing, endings, loss, mourning, and longing.

As these feelings and thoughts echoed in my experience of the paintings, I began to see the cycle as a group of portraits with the flowers standing in for the human figure and the sea becoming time. The “portraits” stood in my studio as witnesses of my own transientness and permanence. So, I should add the word witness to the list above. And, maybe, it’s this witnessing that best describes the awareness of transientness and permanence in all that there is. The witness is the self-conscious bridge between being and not being. Maybe all paintings are primarily witnesses, and what they witness is you and me.

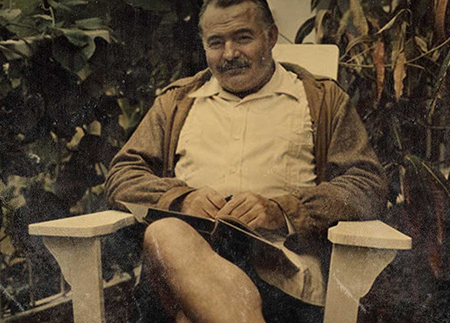

BIRTHDAY ENTRY

June 9, 2022

Today is my birthday, and I am thinking about the people I am grateful to.

When I was a kid, I had a proper estimation of the individual vision, discipline, and resilience it takes to create something meaningful and lasting. My outlook was similar to what Hemingway wrote in his Nobel Prize Banquet Speech,

“Writing, at its best, is a lonely life. Organizations for writers palliate the writer's loneliness but I doubt if they improve his writing. He grows in public stature as he sheds his loneliness and often his work deteriorates. For he does his work alone and if he is a good enough writer he must face eternity, or the lack of it, each day.”

What I underestimated was how much I would need others to be who I am and do what I do. The list of these others is long, and it includes family, friends, partners, teachers, assistants, collaborators, supporters, collectors, critics, curators, gallerists, coaches, people I have barely known, and the thinkers, writers, artists, and scientists that inspire me and have taught me much of what I know. I am indebted and grateful for their vision, discipline, resilience, love, and self-sacrifice. I also have to include those people who have brought obstacles, carelessness, or malevolence to my life, as I have learned much from them too.

In our age, entertainment, distraction, greed, illusion, and narcissism seem to run the show, but the real show is run by love, however rare it sometimes seems.

In Crisis in Culture, Hannah Arendt wrote,

"The common prejudice that love is as common as "romance" may be due to the fact that we all learned about it first through poetry. But the poets fool us; they are the only ones to whom love is not only a crucial, but an indispensable experience, which entitles them to mistake it for a universal one."

I have learned—slowly and often clumsily—that love is the indispensable experience. In art and life.

PIGEON POINT

April 25, 2022

The picture above is Pigeon Point as one comes to it from the south on the Pacific Coast Highway. This lighthouse is where I spent five days in my mid-20s deciding whether to leave physics to devote myself to art. During my time there, I walked the beach, sat on the rocks, and thought. Most of these thoughts took the form of notes on art, physics, and ideas that seemed relevant to life and work. Here are two examples of what I wrote about control,

"Passion is internal fire. Human effort. Possibility made emotion. Passion is not rage or violence. It is control. Avoid consuming feelings that swallow passion and erode your fundamental beliefs. Trust passion. Nurture your ability to be passionate and, for as long as it lasts, go all out. Go beyond what you think is possible. Passion is the ability to believe in something."

"Basic control can be learned by doing your work and by being humble while working on your self-assurance. Seek the usefulness to your life, even if it is of the simplest kind. Simple work curbs dreams of greatness and connects you to the world. By doing what needs to be done, you get rid of possible ways to cut yourself down or stress yourself for no reason."

Those five days were challenging but also expansive. Did you make a decision that changed the course of your life? And how did you go about it?

JOAN DIDION

December 6, 2021

I picked up an old, foxed copy of Slouching Towards Bethlehem at Moe’s Bookstore in Berkeley only because I recognized the title from Yeats’s poem. I was 21, and my version of an Ivy League education had not introduced me to Joan Didion, so I sat on a corner of Telegraph Avenue and read her writing for the first time. Although the book had been published twenty years before, I recognized in her essays the aimless longing, disaffection, and thwarted beauty I felt around me, as well as in me.

People have always been dying, but the deaths of those with good minds and character have felt more doomish in the last ten years, as if we are being left by the ones we need most. Joan Didion is a scarring, cool, factual, and grievous writer, and that is enough reason to read her books. But it might be her willingness to take the world as it is, to accept her share of fuckups, and to keep her skin and heart in the game, that makes her an urgent read in an age when easy answers, self-deception, and lack of accountability are commonplace.

Here is a quote from Self-Respect, which she wrote when she was 27, and that is one of the essays included in Slouching Towards Bethlehem,

“In brief, people with self-respect exhibit a certain toughness, a kind of mortal nerve; they display what was once called character, a quality which, although approved in the abstract, sometimes loses ground to other, more instantly negotiable virtues. The measure of its slipping prestige is that one tends to think of it only in connection with homely children and United States senators who have been defeated, preferably in the primary, for reelection. Nonetheless, character – the willingness to accept responsibility for one’s own life – is the source from which self-respect springs.”

THE TRUTH WILL SET YOU FREE

November 4, 2021

My response to Jesus's saying, "you will know the truth, and the truth will set you free," has evolved over the years. In my teens, I thought, "that sounds right," and that conviction nudged my approach to life and my interest in physics, philosophy, literature, and art.

Then, more life happened—as a proxy for it, the following passage from Hemingway's "A Farewell to Arms" is as good as any,

"I know that the night is not the same as the day: that all things are different, that the things of the night cannot be explained in the day, because they do not then exist, and the night can be a dreadful time for lonely people once their loneliness has started. But with Catherine there was almost no difference in the night except that it was an even better time. If people bring so much courage to this world the world has to kill them to break them, so of course it kills them. The world breaks every one and afterward many are strong at the broken places. But those that will not break it kills. It kills the very good and the very gentle and the very brave impartially. If you are none of these you can be sure it will kill you too but there will be no special hurry."

So, the teenage conviction I once had that truth sets us free shifted to "maybe" or "sometimes." Then, more life happened, and noticing how truth and Truth often break into situations with scorching matter-of-factness and limits, and how truths in the present can change your past making you wonder where you have been, my response to the setting-you-free business became, "truth and Truth matter, but exercise care."

However, I didn't become a cynic or a moral relativist. The reason why I didn't is that the hole left in my conviction of truth's capacity to set me free was partly filled by deep beauty. By deep beauty I mean the recognition of a vast soul becoming art in all its forms (Maeterlinck's book, for instance); or a transformative encounter with the spirit of nature; or experiencing the clear thinking of a taut, expansive mind; or witnessing the manifestation of a tender heart; or confronting an act of courage against all odds; or love.

How about you? Does truth set you free?

JUANITO DELGADO

July 16, 2021

As I was reading and hearing about the brutal repression of the protestors in Cuba and the humanitarian tragedy Cuban people are suffering, I learned my friend, Juanito Delgado, died of Coronavirus complications yesterday. Juanito's death is a terrible loss for those who knew him and for the arts in and out of Cuba. He was a luminous spirit, a champion of art and artists, and he did with a small budget—or with no budget at all—what richer curators and institutions dream of achieving.

The loss of Juanito is made more unbearable by knowing he died as Cuba, the country he loved and fought for, is sunken in despair. The "big picture" of the political situation in Cuba is complex and debatable, but what is undebatable is the catastrophe of seeing Cubans beating Cubans in the streets. The protestors who are being hit, kicked, and jailed, are often willing to die for a fraction of the opportunities we take for granted in the United States. They rise in the streets hungry, after sleeping in a meager shelter, and desperate, and it is in that miserable condition they are brutalized. Their wretched condition is not one week, or one year, or one decade old. Like their desperation, the terrible conditions in which most Cubans survive are transgenerational.

We Cubans are resilient. Perhaps, too resilient. But we also stand up for ourselves and for those we love regardless of the consequences. These protests are not only a cry for better living conditions, medical treatment of the sick and the dying, freedom, and self-determination, but also they are the rising of human dignity in the face of oppression.

The picture above is from 2019. A happy moment when after installing my sculpture, "El trineo," in the Malecón at the invitation of Juanito as part of his program, Detras del Muro in the XIII Bienal de La Habana, Juanito, Jorge Perez, and I posed for a picture. Things were not great for Cuba or Cubans then, but I couldn’t imagine that Juanito would be dead two years later, and Cuba will be confronting another tragedy.

ON POETRY

June 24, 2021

Another posting on poetry. When people explain why they like poetry, I often hear what sounds like emotional and intellectual flacidness—almost as some sort of justification for being imprecise, whimsical, or unaccountable. Or if I hear why someone doesn't like poetry, it is frequently because they see it as obscure and touchy-feely. The views of those who like and those who dislike it agree in that poetry is irrational, fanciful, and driven by an aesthetic imperative.

Seldom do we hear about the resilience, strength, and clarity of poetry. These are descriptions we might use for philosophy or, maybe, fiction. Martin Heidegger, in Nietzsche (Vol 1), writes,

"All philosophical thinking, and precisely the most rigorous and most prosaic, is in itself poetic, and yet is never poetic art. Likewise, a poet's work — like Holderlin's hymns — can be thoughtful in the highest degree, and yet it is never philosophy."

Not all poetry is "thoughtful in the highest degree." Most poetry, like most art, rarely amounts to more than a trill towards meaning. Through some magic trick of cultural expectations, heart deficiency, or incapacity to see through bullshit, we convince ourselves—or someone else convinces us—there is meaning, even clarity, in what is a turbid approximation to meaning or a sentimental impersonation of emotion.

Poetry and art are not affected by these convictions. They are impassive to most human machinations. They are also not swayed by lobbyists who stand behind trite nuances, anemic positions, or bombastic political, artistic, or personal claims. Artists, writers, academics, curators, critics, can be swayed or indoctrinated—usually because there is something compensatory or lacking at their core.

The lameness of most art and poetry we see and read are hard to sum up in an Instagram post, but it is not far off course to say the summing up could start by considering our diminished expectations and our fear of going down, of letting ourselves go to ashes without letting that be fortuitous or glamorous—how tired I am of artists and poets talking about "failure."

Above:

The Measure, 2015

Take a look at the related poems below:

- "Mankind owns four things

- That are no good at sea:

- Rudder, anchor, oars,

- And the fear of going down.”

- — From Proverbios y cantares (xlvii) by Antonio Machado

- There is a singer everyone has heard,

- Loud, a mid-summer and a mid-wood bird,

- Who makes the solid tree trunks sound again.

- He says that leaves are old and that for flowers

- Mid-summer is to spring as one to ten.

- He says the early petal-fall is past

- When pear and cherry bloom went down in showers

- On sunny days a moment overcast;

- And comes that other fall we name the fall.

- He says the highway dust is over all.

- The bird would cease and be as other birds

- But that he knows in singing not to sing.

- The question that he frames in all but words

- Is what to make of a diminished thing.

- — From The Oven Bird by Robert Frost

PABLO GUEVARA

June 22, 2021

Before Pablo Guevara and I spent nights listening to records, I had already been reading for a while. If literature wasn't my friend yet, it was a good companion, though impatient and demanding. I rarely slept out of my house, but I stayed at Pablo's after track practice a handful of times. Those were nights of freedom and nights of music. His father had a collection of records by singers like Pablo Milanes, Paco Ibañez, Silvio Rodriguez, Facundo Cabral, and Carlos Cano. We placed records on the old turntable, waited with excitement for that first scratch of the needle, and listened.

For the most part, I don't remember what we were listening for. We sensed largeness, and that seemed enough. The same largeness I sensed when I read Hesse or Cervantes. But I do remember what we were listening for when we played Joan Manuel Serrat. His voice and his music were an education in feeling for two 15 year-olds. I am not sure feeling is the word. The emotional texture of life and the world? The capacity of the heart?

I had read some poetry before Serrat, but I preferred novels and short stories. The first time we played Joan Manuel Serrat canta a los poetas, we listened while lying on the floor. When the music finished, we stayed like that. Looking up at the ceiling and silent. Poetry became part of my life that night. Following Serrat, I read Miguel Hernandez, Rafael Alberti, and Antonio Machado. Soon after, I ventured on my own to Federico Garcia Lorca, Juan Ramon Jimenez, Gabriel Celaya, Nicolas Guillen, Mario Benedetti, Pablo Neruda, Octavio Paz, and others. I have been reading poetry since.

But reading poetry is not really what I have been doing. I have been using poetry. When I need to see, I turn to poetry to open my eyes. When my heart has been small, poetry has shown me why. When I have felt desolated, poetry has been my shelter and family. When I felt invincible, poetry has hammered me with humility. When I have asked "why should we bother with art?" poetry has offered a convincing answer. When I have felt I can't take one more step, poetry has walked by my side.

Does poetry mean something to you?

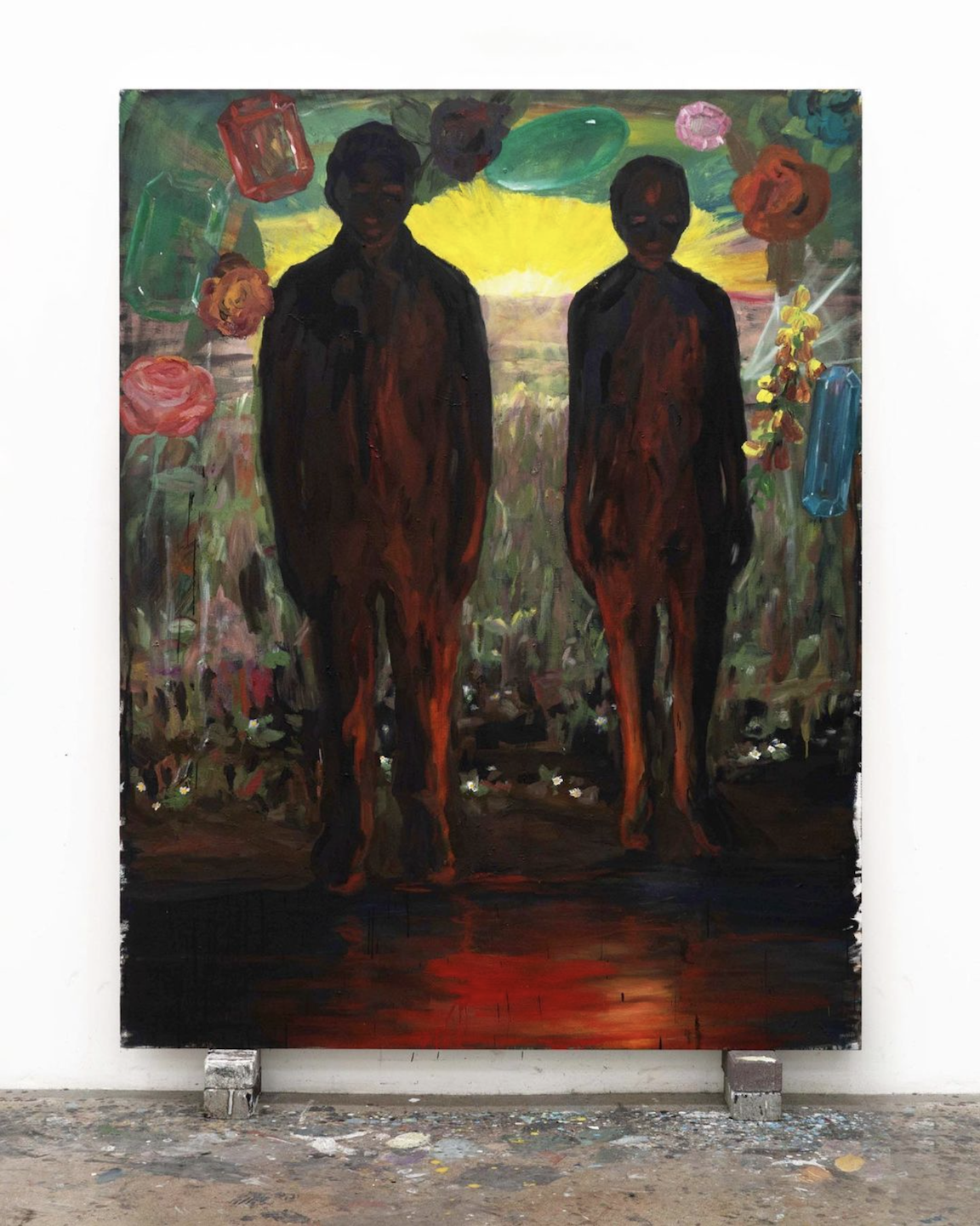

THE COUPLE

March 30, 2021

Here is The Couple again. It is still unfinished. It has been a challenging painting, partly because of the emotional life of what we see in it, but mostly because of my struggles with the nature of painting.

It is not hard to make a painting, but it is hard to make a good one. Painting is not a vessel in which to dump ideas, and it is not a record of the fabulous painting licks one can do. It is closer to a set of tensions (a theology of tensions?) whose manipulation determines how much energy we can store in a work. This energy, in turn, illuminates our darkness.

These tensions are affected by everything; images, surface, edges, context, scale, material, experience, distance, etc. Each work rearranges these tensions to create a cavity of Being where energy is stored. Not letting this cavity collapse involves many battles. I lose most of them—maybe all—and I am not saying this to be charming, sensitive, or modest.

Art is a universe, and artists try to figure out what it is and how it works. The boundaries between emotion and intellect, conceptual and physical, or abstract and figurative, only make sense when one looks at paintings superficially. When considered more deeply, these boundaries dissolve. The complex and mostly unknown dynamics of self, world, experience, and art make achieving a non-trivial work very difficult. The history of art, fascinating as it is, is as helpful to these endeavors as the history of physics is to solving a physics problem.

Making a good painting might be challenging, but that doesn't stop anyone from making facile paintings. There is a cult of bad didactic illustrations from people who mainly see paintings as vehicles for themes and narratives. There is also a tendency to be seduced by a "virtuosity" that is more the result of painting-after-the-projector brushwork than painting power. There is also another type of painting that "surprises" us with a smorgasbord of topical painting delights and mannerisms, usually combined into a "near-fact"—something that doesn't quite add up but has the making of a recognizable thing.

NOTES ON A THIRD OF THE NIGHT

January 21, 2021

- One dark night,

- Fired with love’s urgent longings

- — Ah, the sheer grace! —

- I went out unseen,

- My house being now all stilled.

- —From Dark Night of the Soul by San Juan de la Cruz

There are twelve paintings and one sculpture in A Third of the Night, my upcoming installation at Baldwin Gallery. The project surges from questions about the immutability and remoteness of the world in the face of human problems, uncertainty, and losses. It is also influenced by reflections on the exilic imagination and its longing for home.

I avoid addressing images, themes, and narratives in the work, preferring instead to speak about the intellectual and emotional context in which it was made. For A Third of the Night, however, I would like to say a few things about what I see in the work, though, knowing how easy it is to limit the experience of the painting with words, I hope my writing will not be understood as definite interpretations or explanations of the work.

These paintings and sculptures seem to point to a charged moment when awareness recognizes that something is happening or about to happen. In a journey, this could be the moment of departure, arrival, or recognition that it is the end, as in the painting, The Night, where the figure glances at the horizon as the boat sinks. Is this a glance of recognition of the situation—the unfinished odyssey—or is it the last look at the world and our projections? Whichever the case—and there are many other possibilities—it is a moment of inflection that opens an insurmountable gap between the before and the after. Similar junctures occur in the still skater in The Jump or the confrontation with the self amid nature in The Mirror.

And who recognizes these inflection points as inflections when they are happening? This question has haunted my life and work for many years, and it and the observer it implies, reappear in A Third of Night as a mirror, moons, stars, and birds—all of them witness, all of them watching. Suggested by this awareness and the discontinuity between the before and the after is the question of innocence and the loss of identity in exchange for another. After the dividing moment, the past, the home, and who we were will be out of reach, even if the new has yet to become or materialize.

This trade is familiar to exiles, who exchange a known reality for a projection created by the imagination. The exilic dream promises that the future will be better than the past. Yet, as it often happens, the arrival at the great future, the utopian home, is continuously postponed. Far off course as exiles always are, we search the sea, look for rainbows at the shore, fear the seduction that will detour us, and place flowers at the tomb of who we were and in the altar of what we hoped to be.

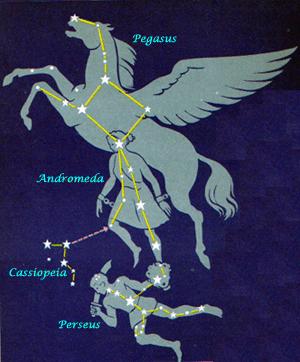

The exhibition title, A Third of Night, comes from the Book of Revelation, 8:12: "The fourth angel sounded his trumpet, and a third of the sun was struck, a third of the moon, and a third of the stars, so that a third of them turned dark. A third of the day was without light, and also a third of the night." At this point in the scripture, three angels have delivered calamities to the earth. Then it is the turn of the fourth angel to bring darkness—confusion, obscurity, shadowy understandings. Two-thirds of the stars still shine, and it is this visible sky I chose to reference in all the works, an intentional visual consistency that is unusual in my exhibitions. Unlike many painters, I rarely use a repeated motif or reference in my projects, preferring a conceptual, emotional, or philosophical throughline.

When I looked at the stars from the shore of my childhood beach town, questions came up about the world, our place in it, and the connection between all things. Back then, the dome of heaven and its relationship to us was a mystery out of the reach of reason—or, at least, not tamed by reason. Even after studying the universe's extraordinary physics, that dome remained charged with mystery, as well as with metaphysics and ethics. In A Third of the Night, I try to acknowledge that mystery and the tension between the sublime sky's epic scale and the smaller scale of our lives, problems, hopes, and feelings. More than a tension, I see the relationship between the two as friction that shapes our understanding of place, destiny, and identity.

But references like stars, sea, birds, or people should not be understood as separate from the materials and conceptual conditions of painting and sculpture. For instance, the crude representation of mirrors, diamonds, stars, transparency, and light in my paintings acknowledges from the onset the futility of "capturing" the world and suggests the aim of art has something to do with the acceptance of that deficit. The paintings are made with roughly applied thin layers of oil and wax that reveal their gesture and physicality even while pretending to render light or a leaf. In the way the work is approached, the etherealness of references is recognized to be in a battle with the earthliness of materials and action, and whatever truce is achieved in each painting or sculpture will be unstable.

Finally, I want to acknowledge my debt to poetry, which continues to inform the type of experience I want from my work. I read and write poetry not so much for content but to shape the emotional and intellectual ambition of what I am doing. While every poet and writer I have read is in some way relevant, in A Third of the Night, Boris Pasternak, Robert Frost, Czesław Miłosz, Harry Martinson, and Robert Lowell were most influential.

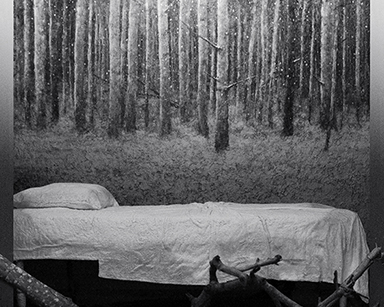

WALDEN

November 9, 2020

[…] if one advances confidently in the direction of his dreams, and endeavors to live the life which he has imagined, he will meet with a success unexpected in common hours. He will put some things behind, will pass an invisible boundary; new, universal, and more liberal laws will begin to establish themselves around and within him; or the old laws be expanded, and interpreted in his favor in a more liberal sense, and he will live with the license of a higher order of beings. In proportion as he simplifies his life, the laws of the universe will appear less complex, and solitude will not be solitude, nor poverty poverty, nor weakness weakness. If you have built castles in the air, your work need not be lost; that is where they should be. Now put the foundations under them.

Where do we find strength, guidance, and clarity to helps us contend with political and social instability, a runaway pandemic, greed and materialism, an environmental crisis, an overt as well as covert exploitation and cruelty of those we consider different or inferior, and the desperation and addiction afflicting so many individuals and households? An excellent place to start is with those two American thinkers, Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry Thoreau. The American empire might be waning, but the American literary, philosophical, artistic, and scientific traditions are not to be dismissed, and Emerson and Thoreau are examples of why people have admired these traditions as well as Americans.

The painting above, The Prodigal Son, is based on the cabin at Walden Pond where Thoreau spent over two years. He later recalled his experience in Walden, which included reflections on the choices we make and the importance of thinking of ourselves as part of nature rather than its rulers. Today, many of us are trapped in cycles of acquisition and arrogance while we compromise our intellectual and spiritual ambition and honesty. On the other hand, Thoreau advocated shedding and simplicity but remaining ambitious and honest in our intellectual and spiritual aspirations. In the conclusion of Walden, he writes (feel free to change all those “he” for whatever pronoun seems right to you),

A NOTE ON TRUST

March 17, 2020

Even though trust is an issue for most of us, the question of who and what do we trust sometimes moves from background noise in our interactions to an urgent, existential threat, and in those moments, our life comes to a crystalline stop. The question taps us on the shoulder looking for an answer when we are all talked out or crawls into bed at night to expand our loneliness. It is our mirror when we are cheated on, devalued, or abandoned, and it becomes our misguided co-conspirator when we decide not to be fooled again. Depending on what you are dealing with, the question of who and what do we trust can wait patiently in the corners of life watching our mightiness, our plans, our hopes, our distractions, knowing the time for the ambush will come.

The world now is confused, and fear spreads. The same people who a month ago were feeling invincible or toasting the markets today panic not knowing what the hell is going on. Those who were a month away from homelessness now fear to lose even that small buffer. Institutions and governments seem lost. In the empty supermarket aisles, the veil of civilization that covers the savage in all of us has thinned and frayed. Will you have enough to eat? Is your job safe? Are banks safe? Are you safe?

Who or what do you trust when so many victories begin to feel pyrrhic? Were they victories at all? Who is keeping tally of the casualties? Did the triumphs make you feel virtuous, and now what? Who or what do you trust when the person to whom you showed even your microbial flora re-invents you and describes you as someone you don’t recognize?

THE OTHER LIFE

April 19, 2018

WRITING AND WORDS

Part of me likes consistency and systems, though I am aware that granular observations and examinations of life patterns undermine the illusion of order. Growing up, dislocation and chaos were more familiar to me than order, and maybe that is the reason for its appeal. This conflict between order and the particulars of experience is commonplace; what differs from person to person is the magnitude of the struggle. In his 1953 essay The Hedgehog and the Fox, philosopher Isaiah Berlin described this tension in Leo Tolstoy:

This violent contradiction between the data of experience, from which he could not liberate himself, and which, of course, all his life he knew alone to be real, and his deeply metaphysical belief in the existence of a system to which they must belong, whether they appear to do so or not, this conflict between instinctive judgement and theoretical conviction–between his gifts and his opinions–mirrors the unresolved conflict between the reality of the moral life, with its sense of responsibility, joys, sorrows, sense of guilt and sense of achievement–all of which is nevertheless illusion–and the laws which govern everything, although we cannot know more than a negligible portion of them–so that all scientists and historians who say that they do know them and are guided by them are lying and deceiving–but which nevertheless alone are real.1

In my case, the desire for consistency and system-building was, and remains, a tendency of my writings about artistic projects. Behind this tendency is the expectation that each new essay or note should have a relationship to previous ones, particularly in their overarching emotional and philosophical tone. This is why I am surprised by the new work, The Other Life, which wants to carve out its own territory. The Other Life has connections to what I have done before, but its emotional register posits more starkly than before despair, loss, and loneliness against tenderness, redemption, and love. As I consider the paintings in this body of work, I find myself reflecting on inevitability, tragedy, and loss in a way that does not discount hope but places it out of reach—an unavoidable and maybe worrisome narrowness of scope that also affects this writing.

This writing is also influenced—and probably made more convoluted—by my desire to challenge what I think are misunderstandings about my work that often stem from ready-made analyses. One motivation for mounting these challenges is the recognition that for me to be clearer, many of the terms and words I want to use need to be repositioned or reclaimed. Words are clustered with associations that influence their meaning. If I say painting, for instance, the word brings with it ways in which paintings are described and considered; or if I say loss, it is usually assumed that as an immigrant I must be invoking exile. Decoupling associations is difficult, however, so we tend to either ignore their clustering around our words, or avoid words altogether by letting “the work speak for itself.” Since our interpretations rely on comparing what we see and hear with what we know, the success of either approach in serving the work depends on how closely its spirit mirrors the contemporary artistic and intellectual discourse. In the case of my work, current biases towards familiar themes and approaches have had at least two detrimental effects on its being understood: the insistence that my project should be examined with the apparatus constructed around exile; and the assumption that everything is secondary to the narratives suggested by the images.

THEORIES OF EXILE

All too frequently, art people expect to tease out the vagaries of self, loss, identity, and other related concepts with the use of an idiom of equivalence—this means that, this leads to that—which is crude in its insights, and cruder still in its revelation of the dynamics of those insights. In equations of dislocation formulated by whack-a-mole philosophies, nuances are displaced by pamphlet politics, packaged phrases, and international biennial themes. These common art idioms and the spirit underneath them strike me as hubris originated in fear. One of these idioms of equivalence revolves around dynamics of displacement and loss. I have been asked, or told, many times how the loss suggested in my work relates or must relate to my exile, a well-trodden analytical path that seems to propose the foreigner is to be considered mostly, and often only, in relation to his or her national dislocation.

Is that so?

Yesterday I saw a woman with lumps of gray wooden hair sitting outside a McDonald’s asking for money. In early March, I had lunch with an investment banker with shark eyes that he uses to look for something he lost a while back. J’s manicured hands rub his thighs as he talks, and now he sleeps in a separate room from his Mayflower wife. A wilting rock and roller lays on me his Native American borrowings while his spirit flaps mournfully in the wind. The vast nothing has opened within them. Their moral aims have grown vague. Are they exiles? I don’t know about the homeless woman, but the others were born here.

Losses, failures, and near misses, as well as achievements and the efforts behind them, exert their weight and their drag on us. Meaninglessness and fancies worm into our drives, whether we are natives or foreigners. Finding oneself in a strange land leaves an indelible mark, especially if brutality, poverty, or sexual abuse are part of the migration, but the emotional equations are different for everyone. Some experiences are shared, but each exile has his or her own story to tell, which may or may not be more acute than his or her other individual psychological, existential, and domestic conditions. Insisting the foreigner’s equations of loss and gain can be solved with the algebra of a displacement narrative oversimplifies. The price usually paid for accepting conventional dissections of who we are is the invisibility of the existential and psychological dimension of our experience, and thus of ourselves.

Where is divorce in the narrative of exile; by which I mean not a social or legal term, but the lived reality of losing one’s grip on the known life, or of looking at one’s kid lost in his twin bed, wondering what the derailment of a marriage will mean to him? Where is poverty; again, not the statistics compiled and discussed in offices, but the shame and hate for the stray cat who took the only meat to come across your plate in weeks? Where is the embarrassment and aloneness of feeling different, not enough, not counted, and not countable? Where in the intellectual framework of exile can I find the means to capture my neighbor rubbing the head of his dick on the picture of my teacher’s daughter, while I stare at my yellow ducklings he drowned in a mud hole? Where is the jargon of translocation that helps me understand my mother’s longing, or my father’s Jules Verne dreams, or the melancholy of the violent and incestuous barrios in which I grew up?

Why would I accept, then, a formulaic exile harness for my losses and hopes? One common reason for accepting it is to have something to hold on to in the elusive-and mostly doomed-pursuits that are art and life.

THE WHALE